China was the nation about which I had the greatest preconceptions before visiting on my journey, and I’m glad and unsurprised to say that many of them have on a local level been wrong. Yes the massive country has a poor human rights record, poor work practices, pollution, overpopulation and is prone to strong-arming and antagonising its neighbours. But, the last two months have reminded me of a lesson I learned two years ago when I visited Iran; the behaviour of a country’s government does not always represent that of the country’s people.

The longer I travel in China the more difficult it has become to narrow down what ‘China’ is or means. There seems to be no such thing as Chinese language, script, cuisine or landscape, each of which varies sometimes wildly between the 55 ethnic groups which share and compose the country. Between the four provinces through which I’ve travelled I’ve barely scratched the surface of all China has to offer but by experiencing some of these minority and rural communities I have witnessed a side of China I never expected to see nor really knew was there and have begun to build an alternative human image of a nation often simplified by stereotypes.

China is a difficult country to traverse by bicycle – particularly if you want to camp. Where the roads are flat it’s often bustling and polluted, but in the mountains and back roads of southern Sichuan and northern Yunnan I stumbled upon corners of the country where the roads were poor, the people kind, the climbing endless and life tended to move at a slightly slower pace than down in the buzzing lowlands.

Chengdu was a city of unexpected delights. It seems at first glance like a smoggy unremarkable metropolis, but once you meet some folks to take you around it has a way of sucking you in.

I was lucky enough to fall in with a group of expats,

and time my arrival perfectly with Elise, an old friend from Melbourne, in Chengdu for the 7th Slow Food International Congress. For the few days when she wasn’t busy with her work it felt amazing and surreal to be back in the company of a friend from home.

Slow days and sleep ins followed late nights out.

The obligatory visit to the Chengdu Panda Sanctuary

with all of the other tourists.

I even found a group of Aussies to watch the AFL Grand Final, complete with Australian beer, wine and sausage rolls.

For almost two weeks Suzie rested peacefully against a wall while I meandered the streets of Chengdu, soaking up the sights, sounds and flavours of this massive city.

Tea shops regularly treated me to drawn out tea ceremonies where I would sit and chat with the shop owners for an hour or so while sampling various subtle and fragrant teas from the region

while being hypnotised and calmed by the poise, grace and precision of the ceremony itself. Everything must be just so.

A healthy dose of immaturity occasionally thrown in the mix.

I was dangerously comfortable after my two week break. I’d built a friendship group, had a favourite noodle and baozi place, and knew the streets of my neighbourhood.

If you are a native speaker it’s very easy to get a job teaching English in China. You can earn around $1800AUD a month and rent a room in an apartment for only a few hundred dollars. I was offered a job in Chengdu without even applying for one and if there wasn’t a time limit on my bike trip I may well have taken the offer and spent a year in town.

Conscious of my promise to my family that I’d be in Melbourne by Christmas though, I eventually tore myself away from the comforts of a potential new home and pushed out of town.

A day of busy roads and industrial districts led south to Mishan.

In the evenings in cities all across China people cart large speakers to public parks and squares to play music and dance. It’s got to be one of my favourite aspects of modern Chinese culture. A single square can be home to four or five dancing groups doing square dancing, line dancing, salsa, ballroom or any other variety, the music from each echoing high into the city skyline as a discordant cacophony.

Some of the dancers are great and seem to be taking it quite seriously…

while others are just there for a laugh.

I was asked to dance by a few people but manage to turn them away until I was approached by an 86 year old woman to whom I just couldn’t say no. As we shuffled around together to our own imaginary beat a small crowd formed to photograph and film the spectacle – the embarrassing results have been filed away in my private collection.

A sunny day was a rare and precious thing amid all the fog (smog?) and hazy cities gave way to hazy farmland

which gave way to hazy hills.

and eventually to some arrestingly beautiful scenes.

A run of bad luck gave me five flats in three days until I eventually identified the tiny metal spike lodged in my rear tyre.

An appealingly tiny road on the map wiggled its way into Sichuan’s southern mountains but my heart sunk when I saw it up close. It’s nice that Chinese roads remain open even when being repaired but it does make for some challenging and muddy riding.

What on earth are they building all the way out here?

At some points the mud was so high it lapped at the bottom of my panniers. I was considering descending back the way I came but was assured by a restaurant owner that the mud ended 10km down the road.

35km later the mud finally stopped and my wheels could spin freely again.

There were dramatic scenes as waterfalls cascaded down the sheer rock face, spilling across my path

and as the road wound higher

I caught distant and beautiful glimpses of untouched China.

This region of China is populated by the 8 million Yi minority people. A tribe of huge diversity, their dress varied sometimes from village to village, the ladies often plaiting their long hair and tying it up in elaborate styles.

While settling into a cheap bedroom in Lewuxiang I was startled when out of the crowd of onlookers a young lady began speaking English, inviting me to eat dinner in her apartment around the corner. She and her friends were government workers stationed in the rural town.

“We work for the government” they tell me.

“What kind of work do you do for the government all the way out here?” I ask

“Government work” they respond.

Fair enough.

They tell me about how boring the town is and how much they all wish they had been stationed in the city while we eat pork, rice and fried strips of potato, and roast nuts over their heater.

The next morning I was up early to make a dash for the mountain’s 3100m summit. This is one of the extremely rare parts of China where you can still find wild Pandas and I kept my eyes trained on the trees, mistaking every white plastic bag for a glimpse the elusive bear.

I stopped regularly to absorb the scenery, rest my legs from the punishing gradient

and appreciate the solitude of the brilliant ascent.

Descending down the far side of the mountain a diversion off the road in search of a campsite leads me to Yi. I asked him if I could pitch my tent past his town, which was little more than five or six simple houses surrounded by cows, goats and pigs, and connected to the main road by a small suspension bridge across a river.

“Meiyou, meiyou” (No, no) he said, waving his finger at me, before ushering me over to his home.

Yi is a farmer and his pigs grumbled and snorted around his small courtyard.

They seemed as surprised to see me as everyone else in the village. Yi had lived here for 42 years and told me he’d never seen a foreigner here before.

He summoned his five children, his wife, brother in law and father and together we sat on stools and prepared soup and rice for dinner. A chicken was slaughtered, butchered and added to the dish. This struck me as being something done to mark a special occasion, particularly when the soup was served and I realised all of the chicken was in the bowl sent to my corner of the room.

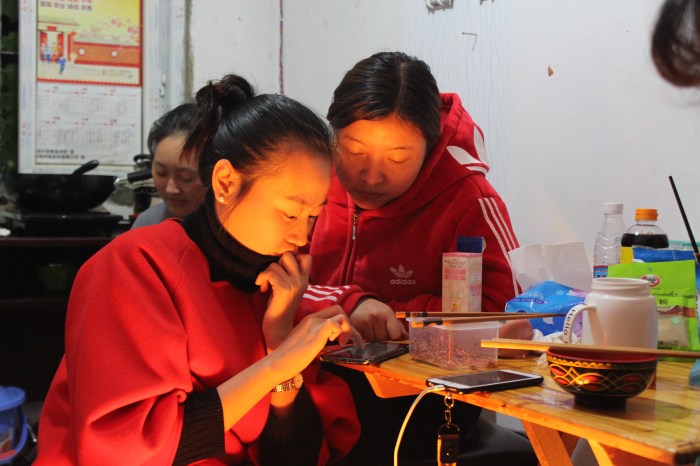

Yi’s kids played games on his phone, toyed with the fire

or were otherwise coddled by their grandfather while Yi and I chatted via my translation ap.

Of the four adults present only Yi could read the phone.

I asked if he liked living in China, to which people usually enthusiastically respond ‘yes’.

“China is not good” he messaged back to me, “We are so poor here. Your country is rich”.

In Yi’s home and eating Yi’s food I was suddenly struck and self-conscious of my privilege, how difficult Yi’s family’s lives must be and yet how unthinkingly kind to me they were in spite of that, and I remained a bit emotional for the rest of the evening.

Dreary weather kept me at the house late into the next morning.

Before leaving I gifted a bag of Chinese sausages I was saving to Yi and his wife and distributed some sweets amongst the kids, slightly embarrassed by how insufficiently my presents represented my gratitude.

I felt surprisingly close to Yi’s family after only a single evening. When it was time to leave Yi walked me back to the suspension bridge and we both endured that awful moment when we shake hands and silently acknowledge that in all likelihood we will never see each other again. It’s a moment I’ve shared with so many kind hearted friends on the road and a part of this style of travelling that I won’t miss when it’s gone.

Back on the road I mulled over the experience for hours. It was beautiful to get an insight into Yi’s family’s life and see how much his children enjoyed playing with a ‘laowai’, but so much of what I saw saddened me. Their poverty was overt and without a good education it’s difficult to imagine how his children are going to break the cycle and leave the farm. China’s Hukou system exacerbates the problem by controlling internal migration. Under the system Yi’s family is registered as living in a particular area and if they move from that area they become ineligible to receive state benefits such as education and health care for themselves and their kids. The system is designed to keep rural people in the countryside and discourage them from moving to cities. Although it is defended as necessary to maintain a rural workforce and prevent urban overpopulation it also aggravates social stratification and denies opportunities to rural communities.

Over yet more mountains on damp, cloudy roads.

To Xichang, the capital of Langshian prefecture, and notable for being on the shores of the apparently beautiful lake Qionghai. To actually get access to the lake costs 50 yuan ($10) though so I skipped it and walked around the rest of the city for free.

Tall apartment blocks,

tiny ridiculous dogs

and bizarrely, an evangelical church were the highlights of my walking tour.

Luguhu Lake; a national park straddling the border of Sichuan and Yunnan, and extremely beautiful if very touristy. Access to the lovely scenery costs 100 yuan but I didn’t know there was a fee until I’d gone all the way there and in a good mood from my first sunny day in weeks I parted with the cash.

Escaping the tourist busses by heading back into the hills, the trees tinged with the unmistakable colours of autumn.

Through the picturesque scenes of rural Yunnan province.

Good misty morning from Yunnan.

And up two brilliant switchbacky climbs that saw me climb over 2000m in a single day to reach Lijiang.

I was in Lijiang to hike the Tiger Leaping Gorge. The city is home to the Naxi minority whose traditional written language is the only surviving example of hieroglyphic text still in use today.

For a day I learned about them from the comfort of my hostel though, my legs too sore from the hills that brought me here to see the town properly.

Mustering only enough energy to nip to the market to buy snacks for the hike.

With mates from the hostel I jumped on a bus to the base of the trail where a gruellingly steep path took us straight up for hours until eventually flattening out,

past pop-up stores selling walking sticks, snacks and bags of marijuana.

Hiking amongst giants, the 20km trail ran parallel to the Yangtze as it cut its way through the gorge

eventually leading to the place where the river narrowed, from where a fabled tiger fleeing a persistent hunter once leapt to safety across the gorge’s expanse.

Pushing my luck. The river roared through the valley and I was transfixed by its violence and power as it forced its way downstream, absorbing all in its path.

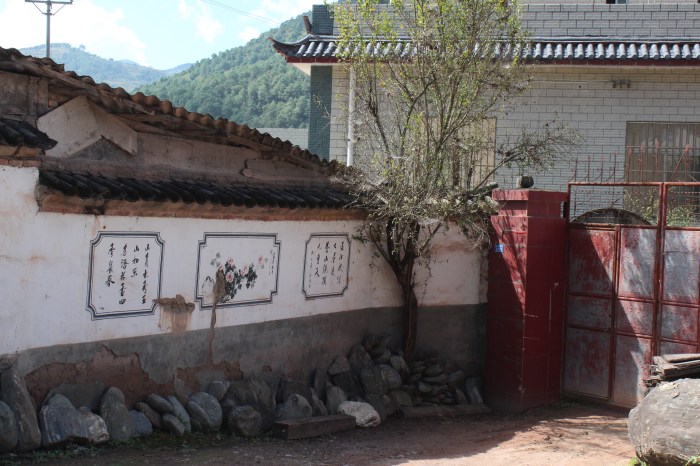

A half day on the bike led me back onto minor roads towards Kunming and through impossibly pretty villages set amongst staggered rice terraces,

where friendly folks go about their business tending to their fields,

and lovely painted murals adorn the walls of homes and businesses.

Life was slower and the hills less steep and I even found a few secluded campsites to spend a quiet night.

Along the way I turned 26 years old but other than a quick call home (I share my birthday with my Mum) it was a day like any other. Eat, sleep, ride, repeat. My Dad reminds me that when he was 26 he had already been working for 10 years.

Don’t worry Dad, I’ll be a productive member of society soon enough.

I have a new system for ordering lunch these days. Rather than trying to decipher the Chinese menu I tell the chef to cook me whatever they want, but I don’t want to pay more than 20 yuan ($4). Ive had some delicious surprising meals this way.

The organised chaos of a Chinese kitchen.

Leaving lunch on my birthday I noticed a calendar on the wall with an image of the iconic Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul and was immediately transported back eight countries and seven months ago to the city where my trip began. When I think about how far I’ve come and everything I’ve experienced since those first nervous and frightening days in Istanbul my journey seems completely unbelievable. I’ve been reflecting on it more and more as my end date draws nearer.

I’m in Kunming now, comfortable and in the good company of Vera, a Dutch lady who with her partner last year completed a bike ride from Amsterdam to Tokyo. She has settled in Kunming for a year teaching English, writing and pursuing her artistic aspirations.

I’ve been reading her blog for tips and directions along my own route and meeting her in person is for me almost like meeting a minor celebrity.

From here my East Overland journey turns southwards as I bid a sad goodbye to China and venture into the dense jungle and punishingly steep dirt roads of laid-back Laos, inching my way slowly home.

Hi Perry Pop. Of course we miss you but we would never deny you the treasure of these amazing experiences. Love you. Another completely beautiful post. We are so proud of you and the young man you have become. Mum and Dad

LikeLiked by 1 person

Happy Birthday Perry! Gosh seven months now – the experiences you have shared with us I treasure as I read.. Safe riding and thank you for these amazing posts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If I had 5 flat tyres in 3 days I think I would cry for 5 days 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another spellbinding read, and photos that would be at home in a National Geographic. I am not even going to ask about the photo of you suspending above a raging river!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You must have changed your plan if you’re going thru Laos! I’m currently in Thailand, heading towards Cambodia. Hope there’s no more flats in your future (nor mine, she adds selfishly)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah I rarely plan more than a few weeks ahead. And even those plans are usually subject to change.

I’m in Bangkok now waiting for my flight home, and from photos I’ve seen from backpackers rural Thailand looks beautiful. Cambodia though looks difficult – hope you are enjoying it!

LikeLike

Well, safe travels! I haven’t seen much of Cambodia yet, but am hoping to enjoy it. Meanwhile, take care, and if that’s the shirt you bought in change that you’re sporting in Laos, it’s looking good!

LikeLike